From their perspective, I imagine it seemed like a bit of fanfare. The loud, long honk of a car horn and soon thereafter my walking in, hot and flustered.

From my perspective, I walked into a sweet-smelling serenity, a stark contrast to the near miss I had just experienced in the parking lot. A woman swung her SUV wide as she backed out of her parking spot, such that she nearly scraped along my driver’s side. If I hadn’t laid on my horn, she would’ve.

“Sorry,” she waved. Or maybe the wave meant, “Alright, alright! Calm down.”

She was a silhouette. I couldn’t tell if she was young or old. A gemstone on the ring of her waving hand caught a brief flash of the sun, and then she drove away.

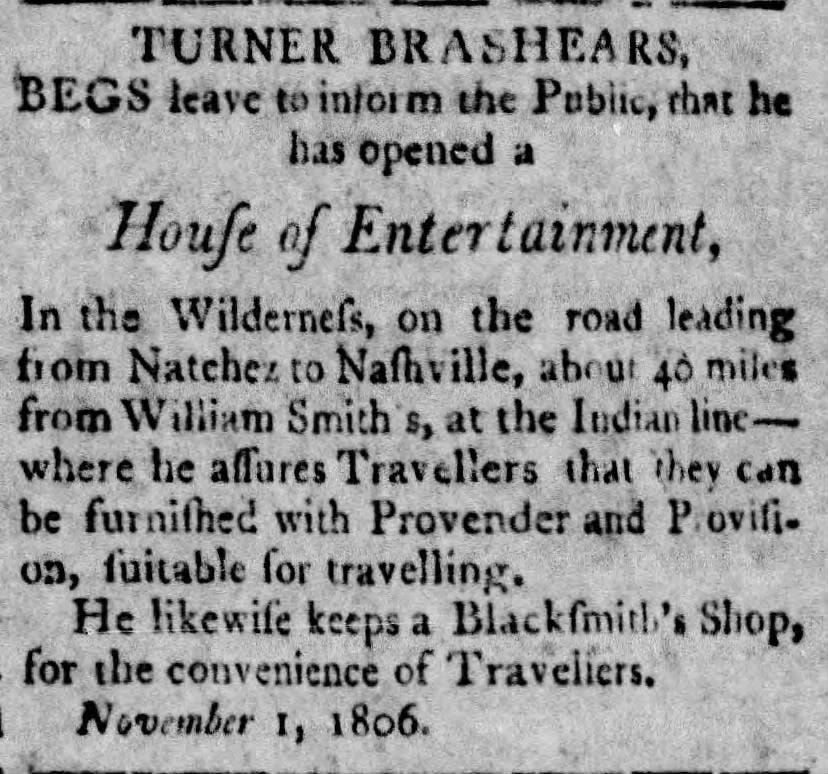

I came to Palladium on recommendation from a friend. I had admired a print hanging over her fireplace—an oil painting of the old Sunken Trace, an ancient, dirt remnant of the Natchez Trace, this winding forest highway that runs from Mississippi to Tennessee.

Two or three years ago I burst out onto the Sunken Trace after fighting my way through a half mile or so of thick brush. I had meant to come to it via the six-mile Rocky Springs trail, but the way had been neglected—technically, it was closed—yet still I was determined to hike it.

I lost the trail half way in and forged a new path, which brought me out onto the ancient road fighting for my life with twigs in my hair, and I startled a little troop of boy scouts who had come marching down the thoroughfare by way of some sanctioned route, their compasses swinging on their backpacks. I bid a good afternoon to the troop leader, a middle-aged man in a bucket hat. I felt it necessary to be pleasant—conversational—so that he would think I wanted to be in this situation. That I was perfectly happy with the decisions I had made all day. That I had not regretted ignoring the “Closed” and “Unsafe for Hiking” signs at the abandoned trailhead.

“So, I guess I just go down this way,” I said as I wiped a spider web from my face, “and come out to the campgrounds?”

In similar fashion, I burst onto the scene of the consignment shop, named after a chemical element or an asteroid. The bumper of my car was mere feet from the storefront window when I put all my heart and soul and weight into my horn.

To my surprise, though, almost no one seemed to notice me. Only the proprietor, who was in the middle of a quiet conversation, briefly broke away and bid me welcome. Then she returned to the woman—a customer, but also, I think, a friend—and a conversation of whispers.

Palladium is made up of several rooms of consigned goods. I began the serpentine route as created by walls that seemed nearly arbitrary. I was in search of a print like my friend’s. Not the same print, obviously, but maybe another Mississippi scene that would be loaded with stories, ancient and new. Something I could hang in my living room or kitchen that would evoke some kind of remark from a guest, which would then enable me to say, “You know, interesting story about that—” and off I’d go.

I got the impression that this place was once a warehouse and that rooms came later—gradually— like I imagine bees would build cells of honeycomb. Someone would want to start up a booth of vintage Fiesta ware and worn oriental rugs, and walls would just go up. That, in turn, made for a very winding, unpredictable route during which I had to constantly look behind me to take in the hidden pockets of art and furniture nestled there.

In this similar fashion, people sprang upon me. Two women came out from behind an old china cabinet as if through a portal. We passed on either side of a velvet sofa, and I found they were talking about someone’s heart condition.

“She had to have a watchmaker implanted in her chest,” one said to the other.

“A pacemaker?” asked the other.

“Her heart would beat too slow, so they put in a watchmaker to regulate it.” Her friend didn’t bother to correct her again.

In another room was an actual art gallery, the part of the store not consignment and also the most traditional layout. Perhaps the only space in Palladium that is and has always been a room. It’s square and adorned in square art. The curator sits in an encased box that looks like a ticket booth. She appears to be 75 or 80, with fiery red hair like Heat Miser from that weird, Rankin-Bass, stop-motion Christmas movie.

“You know she died recently,” I heard her tell a woman at her counter.

“Really,” the woman gasped.

“Just last week. In fact, the memorial service will be right here. In this very room.”

“Wonder if that will drive up the prices of her art,” the other woman said in a lower voice.

“It will. It will.”

To leave this place by the way I entered was an unraveling process. I had to pass by rooms and people I had already encountered. I caught consigned items I missed, even though I thought I had been diligent to check all the acute corners. Also I caught where the stories had wandered. When I came back round to the proprietor at her counter, she and the customer were now talking, more loudly, about a car show that meets every year on the Gulf Coast.

“Me and my stepmother have been taking my daughter down to those shows ever since she was six months old. She’s been riding in a ‘67 Mustang with no A/C since she was an infant. And she’s used to it. Got no choice, though, does she.”

The inexplicable angles and turns of both this place and the conversations in it made me think of the woman in the parking lot. Her only story was one that I extracted from her, and that was the tale of her being wealthy and perhaps not a very good driver. For some reason, my being in the same space where she had been only minutes earlier and getting a glimpse of other people she had merely coexisted with suggested a mysterious new depth to her. A complexity of numerous cuts, like her diamond ring.

I admittedly felt bad now about honking my horn, because I had believed her to be a nobody. Now I was getting the hint that she was a little bit of a somebody, like all the somebodies in the consignment store talking and offering very small glimpses into their winding lives. And if I had been in the store only a few minutes earlier, it’s possible I would’ve heard her talk—perhaps about her granddaughter or her diabetic cat—and she’d still be a stranger to me. But she’d also be more than the flat existence I had made up for her.

Would I have then not honked at her? Would I have let her sheer my mirror and side window and doors off my car like peeling back the lid of a sardine can? Well, no. I don’t think it would’ve changed my reaction one bit. But when I had first pulled up to this place, I saw and chose to ignore the warning sign: the woman’s hulking vehicle as it jutted out at an angle, its back right tire across the white line. I chose conflict. You can do that and enjoy blasting the horn of vindication when the other person involved is almost entirely made up.

Here’s now all that I know of the woman—thanks, in part, to the people she had in some way been membered to: she nearly scraped the broad side of another vehicle in the Palladium parking lot. She was not the deceased painter whose work was climbing in value. She either was or wasn’t the stepmother who rode with her family down to the annual car show in a hot Mustang. She was or was not the woman with the watchmaker in her chest.

I still can't get over the art curator sitting in a box like the fortune teller thing from Big.